„The Word is written in order to be lived the very moment it is being uttered, in direct relation with the sound, with an infinity of states and moments, just like Music does. The Word exists by itself. It comes from somewhere, it lives and then it disappears.

We feel its vibration. And we hold on to it. We can make it vibrate within us. ”

(Andrei Şerban)

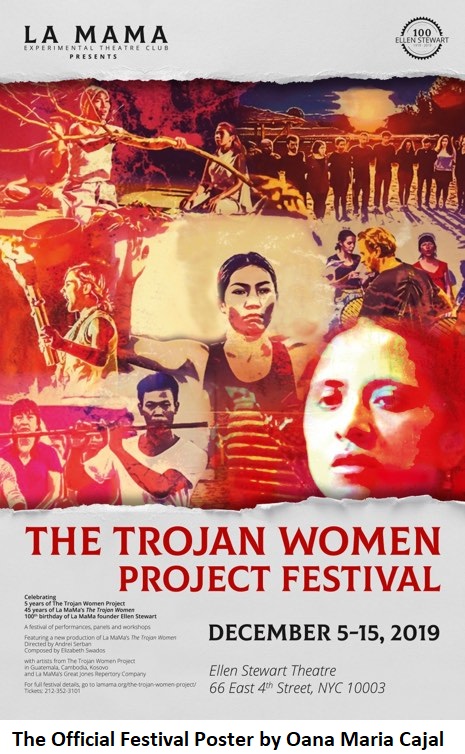

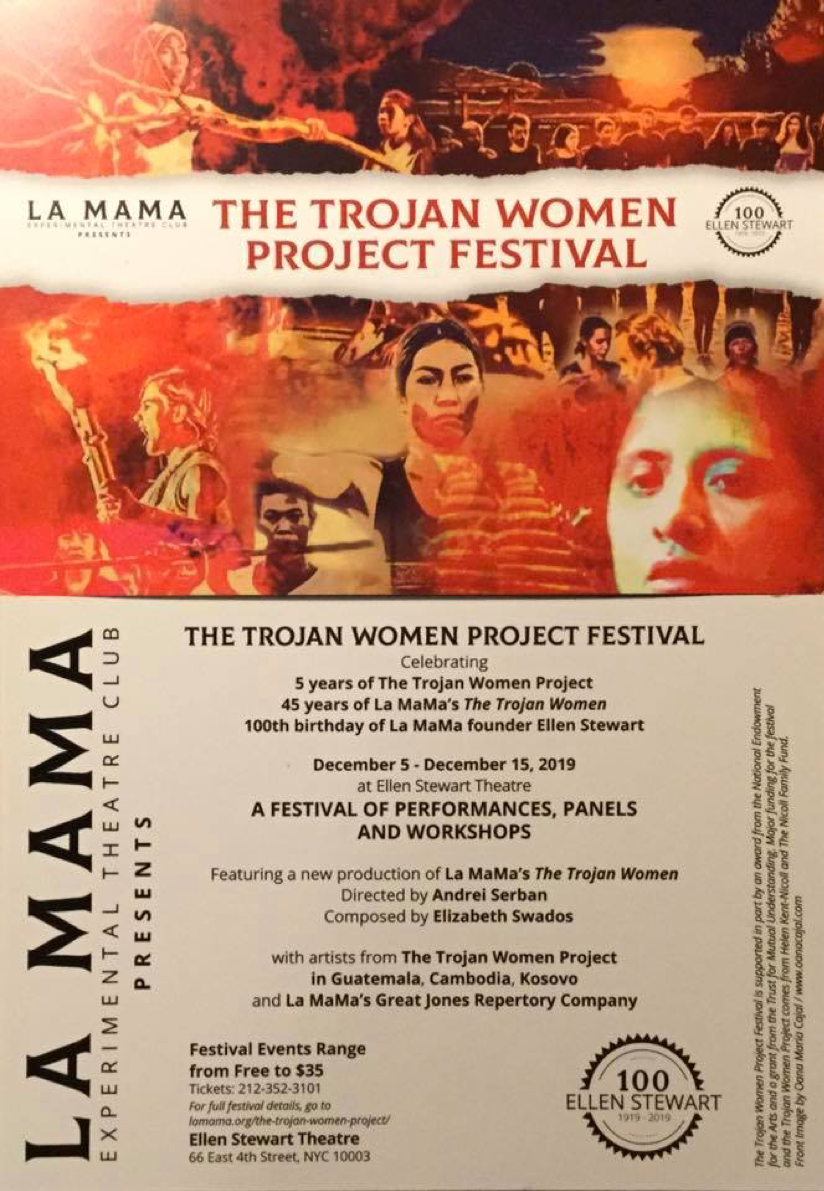

The Trojan Women, the groundbreaking theatrical performance of director Andrei Şerban who revolutionized the American Theater in the 1970’s, reopens this December at LaMama Theater in New York, marking the centennial of its founding figure, the celebrated Ellen Stewart. This Great Lady of the Theater, whose generosity and vision have inspired generations of artists, gathered everyone under her wings and offered actors and directors from all over the world of theater an unconventional framework to “live” and to “perform” at the highest standards of freedom and professionalism. The Trojan Women now belong to the personal history of LaMaMa as well as to the great history of Theater, inspiring generations of creators, opening the public’s taste for Theater as catharsis, as a privileged path to self-knowledge and as an original means of investigating reality. In the West, The Trojan Women represent a chapter by themselves, travelling around the globe, gathering artists and creative energies with a wide variety of cultural, religious and ethnical backgrounds. These days in New York, The Trojan Women Project Festival reunites artists from the original production as well as artists from Cambodia, Kosovo and Guatemala, a proof that The Trojan Women are also a way of enjoying diversity, bringing together different people, their stories and the rich experiences that inspired them.

At the beginning of the 90’s, Trojan Women were a landmark in national theatre. The show directed by Andrei Şerban, at that time Director of the National Theatre in Bucharest, represented a groundbreaking event in an ambitious project whose purpose was to renew the Romanian Theater, freed at last after the fall of Communism from the burden of ideology and old mentalities. Despite their tremendous success at that time, the Trojan Women only came back on stage in 2012 at the National Opera in Iasi, in a new staging featuring Elisabeth’s Swados original music. Thus, Trojan Women are more than just a theatrical performance; inspired by Euripides, Trojan Women are a living story, a tapestry weaving in its threads all those who are willing to participate in Theatre as a direct form of artistic communion, a purifying experience, a personal attachment to the immemorial cultural and psychological strata which define our shared humanity.

Nowadays we cannot be sure what the Greeks understood by Theater, how their plays were interpreted. A few years back, while visiting the ancient Amphitheater at Epidaurus, I became aware of the fact that Theater was part of a complex dedicated to God Asclepius, the healer. Thus, Theater was inseparable from the purifying rituals; it represented a direct participation to a collective experience meant to restore the balance of body and soul, to heal the human person in order to give it back to its community, as part of a living organism. This conception seems to contradict contemporary individualism, as well as the alienation of the self, fragmented and lost in the global city. Still, Trojan Women show us how Theater can become an extraordinary time travelling vehicle, which allows us to unchain locked energies within ancient texts, in order to recuperate founding spiritual experiences and make them our own, in today’s world.

The Trojan Women come from an archaic world of rituals and sacred energies; they speak to us in an ancient language that resonates deep within ourselves, emanating from the elements of nature, from the mysterious symbols unraveled by the director’s labor who, as a fine archeologist, leads us to the complex strata hidden underneath. Trojan Women have the coherent construction, the precise technical execution, the dramatic force of a ritual. We enter their world as crossing the threshold of a sanctuary. Just as we are being reminded, by all theologies, that we all have a universal priesthood. Andrei Şerban has brought to life a liturgical Theater. Trojan Women take hold of us, an overwhelming presence both auditory and visual; an outburst of freedom constructed on rigor, discipline and intensity. Even before the performance begins, spectators enter the backstage, a space delimitated from the main stage, suggesting we have to integrate into an inner world, quite different from the outside realm. Some will try to understand, others will make an effort to participate. Certainly, the ritual is a living reality, where nothings grows old nor out of fashion. Perhaps everything started with Peter Brook’s advice to young Andrei Şerban to stage a play in a forgotten language; indeed, director Andrei Şerban has uncovered a universal language, an Esperanto of sacred theater. The language of The Trojan Women functions as a liturgical language that is not reduced to words but includes incantation and the presence of sacred objects, torches, flames, totems. The entire choreography between the master of sacred ceremonies and the believers – meaning us, the spectators, is composed of assumed theatrical gestures, which invoke and provoke our participation. Every soloist, from Hecuba, Andromache, Achilles, becomes, as a certain moment, the Great Priest celebrating the Mystery of Theater.

Decades after their miraculous birth on stage, it is necessary to ask ourselves how the contemporary individual perceives the world of the Trojan Women; this modern man, the “Magritte serial individual” for whom Ritual is mere a set of ancient regulations, not an existential landmark. However, here lies the provocation of director Andrei Şerban and his unique vision of the world behind the curtain. The originality of The Trojan Women comes from the fact that they dissipate the modern, romantic aura of ancient myths, without tearing apart their core essence. We can always have a cultural experience of ancients Myths, enriched but also devitalized by an excess of added information. But there is another way towards Myths, based on decanting, on carefully separating the different strata obscuring them – to touch the depths of the human soul, to listen to its reverberations. The Trojan Women follow this second path, of kenosis. Answers concerning human nature are to be found by participating into something mysterious, transmitted to us beyond words. We need Theater as Happening, that is a moto dear to Andrei Şerban, familiar to those who have worked with him, of have been trained by him, at the Columbia University or on stage. How can we participate in the dimension of the Sacred, without an intelligent emotion? How does emotion become intelligent? By practical experience, by sharing rituals leading to the mystery of all in one. This search continuously renewed by Andrei Şerban in different stagings of The Trojan Women, resonate with the questions asked by Peter Brook, taken one step forward: „What is the relation between verbal and nonverbal theater? What happens when the sound and gesture become word? What is the role of the word within the theatrical expression? Is it vibration? Is it a concept? Is it music? Is there within the structure of the sound a forgotten language?”

What is the meaning of compassion, love, beauty, sacrifice, oppression, exile? Each of these fundamental human experiences have been altered by our romantic transcriptions. The Trojan Women bring forth a different perspective, allowing us to reposition ourselves with regard to these experiences, in order to understand them, to escape indifference, fear. Thus, to what extent can Greek Tragedy become an experience of Emotion, not just Intellect? How do we rediscover the human Person, the personal dimension of the other? Hecuba, with her royal tiara and her impressive voice seems to be the prototype of Greek women, proud and fearless, profoundly mysterious in their feminity. They know exactly who they are which part they fulfill in their community. They live according to rituals, communicate in a language that uses imprecations and symbolic gestures; they are fantastic storytellers, unravelling their mythology as they weave the canvases of the ships taking them far away into exile. Everything is word and meaningful gesture, ancient traditionpassed along generations. Although powerful and vocal, these Women of Troy possess the art of whispering. Just as women in old rural communities would whisper prayers into their children ears, in order to chase evil and tame the spirits. However, there is a nuance, made evident by Andrei Şerban: the world of the Trojan Women is not Ranevskaia’s Cherry Orchard, revisited with novelistic melancholy; this is a living world addressing contemporary dilemmas; a world which continues to be, here and now. The Trojan Women give us the strength to live in the present.

In a world of conquering men, how powerful the Trojan Women are… even in captivity! Because they represent something together, their strength emanating from the collective whole they give a soul to. Their unity is not monolithic, ideological, but a living, breathing chain of Being, based on the continuity among generations, fed by sacrifice and creative energies. Their hieratical gestures, the costumes with their simple and sober poetry remind me of the heights of the Acropolis, lightened by the sun. As the Women mount the wooden scaffolds, we feel their fear but also their determination. Together they create a realistic human landscape, endowed with exuberance, vitality, sensuality. Far from making us feel sorry for the frailty of faith, their courage is mobilizing. Andromache washes her son’s body, preparing him for death, like in a “pagan” baptism, a water anointment. The collective weeping unites their bodies into a general overflowing, an organic expression of solidarity, beyond reason and language, down to mother Eve. The rape of Helen is an act of divine justice. The women extract a rotten organ from their collective body, as an act of redemption. Sequences like the “dance of the rope” tying down and humiliating Cassandra, or the “rape dance ritual”, made me think that, besides the current aesthetics, there is a paradoxical esthetic of Cruelty. For the Ancient Greeks, as in traditional, archaic communities, cruelty had its regulatory role, in order to purify and restore a human balance as through “the sword and the fire”. The “Ghost” of Achilles reminded me of the traditional dance of the Masks on New Year’s Eve. Another memorable scene is the one in which the Vestal stabs herself, sliding down the scaffolding – a modern counterpoint. In the 1974 staging, there was a weaving woman, a magical Clotho whispering with her spinning in the language of entrails and mysteries. The incipit of the performance, in the back-stages, deep down into the layers of our collective subconscient transforms the scenography into an initiatic path. The road to Troy is the path to Myth. A universe inside which we are called to function as a whole; in order to survive, one must learn to find its proper place and to belong. Afterwards, the passage across the stage down into the theater hall is a salutary anchorage into the present. The theatrical convention and the ritual communicate naturally; passages are exempt of asperities, there is no fracture between worlds. Everything flows and grows, as the dough of a dream; a lucid dream as a premonition, a prophetic trance of Cassandra. The Trojan Womenhave the coherence and the unity of a fairytale, a parable for modern times. Each fragment becomes a concentrated human experience among which, perhaps the most poignant one remains that of exile. No theater has ever created an image so beautiful as the one of the Trojan Women giving a body with their own bodies to the sailing ship. To the waves. To Silence.

It would be interesting to discover how Greek Tragedy dialogues with the American spirit of today. The newly imagined Trojan Women of director Andrei Şerban will most surely provide a fresh answer. However, I believe that regardless of times, Americans will have, perhaps even more that the Europeans, a strong reaction to The Trojan Women, a special empathy to their world of sacred rituals. Maybe in America, where people still arrive from all over the world, the need for roots will always grow, if not greater than before. We are less and less free. And all the more lonelier. Only the anchorage into the Sacred can fully free us, achieving unity with the others as well as within ourselves. Although apparently rough, perhaps sometimes cruel, The Trojan Women is an outstanding performance of Living Theater, filled with Poetry and Beauty. Like the silk canvas my grandmother Anica would weave, as the threads of light and time traversed it, without ever making it loose its vivid colors. The Women of Troy fight to the death with their destiny, just like Jacob fought with the Angel of God. If Euripides gave the Trojan Women a name, Andrei Şerban gave them a Soul.

Troienele, 1974

Troienele (TNB, 1990)

Troienele, Opera din Iaşi, 2012

Troienele, Opera din Iaşi, 2012

Ellen Stewart, founder of LaMama Theatre in New York and director Andrei Şerban

The Romanian version can be accessed here: https://revista22.ro/cultura/troienele-lui-andrei-serban-la-centenarul-teatrului-lamama-din-new-york